Dual curve

In projective geometry, a dual curve of a given plane curve C is a curve in the dual projective plane consisting of the set of lines tangent to C. There is a map from a curve to its dual, sending each point to the point dual to its tangent line. If C is algebraic then so is its dual and the degree of the dual is known as the class of the original curve. The equation of the dual of C, given in line coordinates, is known as the tangential equation of C.

The construction of the dual curve is the geometrical underpinning for the Legendre transformation in the context of Hamiltonian mechanics.[1]

Contents |

Equations

Let f(x, y, z)=0 be the equation of a curve in homogeneous coordinates. Let Xx+Yy+Zz=0 be the equation of a line, with (X, Y, Z) being designated its line coordinates. The condition that the line is tangent to the curve can be expressed in the form F(X, Y, Z)=0 which is the tangential equation of the curve.

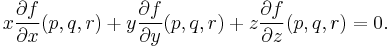

Let (p, q, r) be the point on the curve, then the equation of the tangent at this point is given by

So Xx+Yy+Zz=0 is a tangent to the curve if

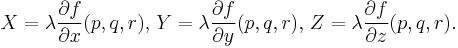

Eliminating p, q, r, and λ from these equations, along with Xp+Yq+Zr=0, gives the equation in X, Y and Z of the dual curve.

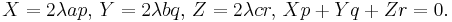

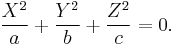

For example, let C be the conic ax2+by2+cz2=0. Then dual is found by eliminating p, q, r, and λ from the equations

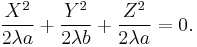

The first three equations are easily solved for p, q, r, and substituting in the last equation produces

Clearing 2λ from the denominators, the equation of the dual is

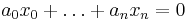

For a parametrically defined curve its dual curve is defined by the following parametric equations:

The dual of an inflection point will give a cusp and two points sharing the same tangent line will give a self intersection point on the dual.

Degree

Smooth curves

If X is a smooth plane algebraic curve of degree d>1, then the dual of X is a (usually singular) plane curve of degree d(d − 1) (cf. Fulton, Ex. 3.2.21).

If d > 2, then d−1 > 1 so d(d − 1) > d, and thus the dual curve must be singular, by duality, otherwise the bidual would have higher degree than the original curve.

For a smooth curve of degree d = 2, the degree of the dual is also 2: the dual of a conic is a conic. This can also be seen geometrically: the map from a conic to its dual is 1-to-1 (since no line is tangent to two points of a conic, as that requires degree 4), and tangent line varies smoothly (as the curve is convex, so the slope of the tangent line changes monotonically: cusps in the dual require an inflection point in the original curve, which requires degree 3).

Finally, the dual of a line (a curve of degree 1) is a point (the tangent line is the same at all points, and agrees with the line itself).

Singular curves

For an arbitrary plane algebraic curve X of degree d>1, its dual is a plane curve of degree  , where

, where  is the number of singularities of X counted with certain multiplicities: each node is counted with multiplicity 2 and each cusp with multiplicity 3 (cf. Fulton, Ex. 4.4.4).

is the number of singularities of X counted with certain multiplicities: each node is counted with multiplicity 2 and each cusp with multiplicity 3 (cf. Fulton, Ex. 4.4.4).

It is known that the bi-dual curve to an algebraic curve X is isomorphic to X in characteristics 0.

Classical construction

If C is a curve in a real Euclidean plane  , there is a beautiful classical construction of a dual curve

, there is a beautiful classical construction of a dual curve  (cf., for example, [Brieskorn, Knorrer]). It uses the notion of inversion and polar curve.

(cf., for example, [Brieskorn, Knorrer]). It uses the notion of inversion and polar curve.

Let S be a (real) unit circle  , and assume one is given a point p inside S. Let l be a line through p orthogonal to the radius through p. The line l intersects S at two points, say, a and b. Let

, and assume one is given a point p inside S. Let l be a line through p orthogonal to the radius through p. The line l intersects S at two points, say, a and b. Let  be the intersection point of tangents to S at the points a and b. Then p and

be the intersection point of tangents to S at the points a and b. Then p and  are said to be inverse to each other with respect to the circle S. Let

are said to be inverse to each other with respect to the circle S. Let  be a line through

be a line through  parallel to l. Then the line

parallel to l. Then the line  is said to be polar to the circle S with respect to the point p, and l is said to be polar to S with respect to the point

is said to be polar to the circle S with respect to the point p, and l is said to be polar to S with respect to the point

Now, if p is on a curve C, and l is tangent to C at p, then one can see that  is a point of the dual curve

is a point of the dual curve  The converse is also true: if

The converse is also true: if  is tangent to C at

is tangent to C at  then

then  is a point of

is a point of

Algebraically, if a is the distance from 0 to p, and  is a distance from 0 to

is a distance from 0 to  then

then  ,

,  as vectors, and, if

as vectors, and, if  , then

, then  has an equation

has an equation

From the last formula one can see that ![p = [l]](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/986325738a93a7b8abf6727132f72d30.png) , i.e., p is the class of the line l if we identify the plane

, i.e., p is the class of the line l if we identify the plane  and its dual.

and its dual.

Properties of dual curve

Properties of the original curve correspond to dual properties on the dual curve. In the image at right, the red curve has three singularities – a node in the center, and two cusps at the lower right and lower left. The black curve has no singularities, but has four distinguished points: the two top-most points have the same tangent line (a horizontal line), while there are two inflection points on the upper curve. The two top-most lines correspond to the node (double point), as they both have the same tangent line, hence map to the same point in the dual curve, while the inflection points correspond to the cusps, corresponding to the tangent lines first going one way, then the other (slope increasing, then decreasing).

By contrast, on a smooth, convex curve the angle of the tangent line changes monotonically, and the resulting dual curve is also smooth and convex.

Further, both curves have a reflectional symmetry, corresponding to the fact that symmetries of a projective space correspond to symmetries of the dual space, and that duality of curves is preserved by this, so dual curves have the same symmetric group. In this case both symmetries are realized as a left-right reflection; this is an artifact of how the space and the dual space have been identified – in general these are symmetries of different spaces.

Generalizations

Higher dimensions

Similarly, generalizing to higher dimensions, given a hypersurface, the tangent space at each point gives a family of hyperplanes, and thus defines a dual hypersurface in the dual space. For any closed subvariety X in a projective space, the set of all hyperplanes tangent to some point of X is a closed subvariety of the dual of the projective projective, called the dual variety of X.

Examples

- If X is a hypersurface defined by a homogeneous polynomial

, then the dual variety of X is the image of X by the gradient map

, then the dual variety of X is the image of X by the gradient map  which lands in the dual projective space.

which lands in the dual projective space.

- The dual variety of a point

is the hyperplane

is the hyperplane  .

.

Dual polygon

The dual curve construction works even if the curve is piecewise linear (or piecewise differentiable, but the resulting map is degenerate (if there are linear components) or ill-defined (if there are singular points).

In the case of a polygon, all points on each edge share the same tangent line, and thus map to the same vertex of the dual, while the tangent line of a vertex is ill-defined, and can be interpreted as all the lines passing through it, with angle between the two edges – regardless, the map from the vertex is ill-defined. This accords both with projective duality (lines map to points, and points to lines), and with the limit of smooth curves with no linear component: as a curve flattens to an edge, its tangent lines map to closer and closer points; as a curve sharpens to a vertex, its tangent lines spread further apart.

Notes

- ^ See (Arnold 1988)

References

- Arnold, Vladimir Igorevich (1988), Geometrical Methods in the Theory of Ordinary Differential Equations, Springer, ISBN 3-540-96649-8

- Hilton, Harold (1920), "Chapter IV: Tangential Equation and Polar Reciprocation", Plane Algebraic Curves, Oxford, http://www.archive.org/stream/cu31924001544216#page/n76/mode/1up

- Fulton, William (1998), Intersection Theory, Springer-Verlag, ISBN 978-3-540-62046-4

- Walker, R.J. (1950), Algebraic Curves, Princeton

- Brieskorn, E.; Knorrer, H. (1986), Plane Algebraic Curves, Birkhauser, ISBN 978-3-764-31769-0

See also

|

|||||

![X[x,y]=\frac{y'}{yx'-xy'}](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/e194332d41ee7f040451d40342960eea.png)

![Y[x,y]=\frac{x'}{xy'-yx'}](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/451f8ceefba3042f3e6119278270d864.png)